You run the same rsync command, but this time the process is over in a fraction of the time it took the day before. The next day, after working on several different files throughout the day, you wish to repeat the process. You run rsync, and soon (depending on the amount of data you're copying), your home directory is now safely copied to your server. You configure rsync so that /home/username is your source directory, and /mnt/server is your destination. The server is mounted, using Samba, to /mnt/server. Here's an example: let's say you want to backup your home directory-at /home/username-to a server on your network.

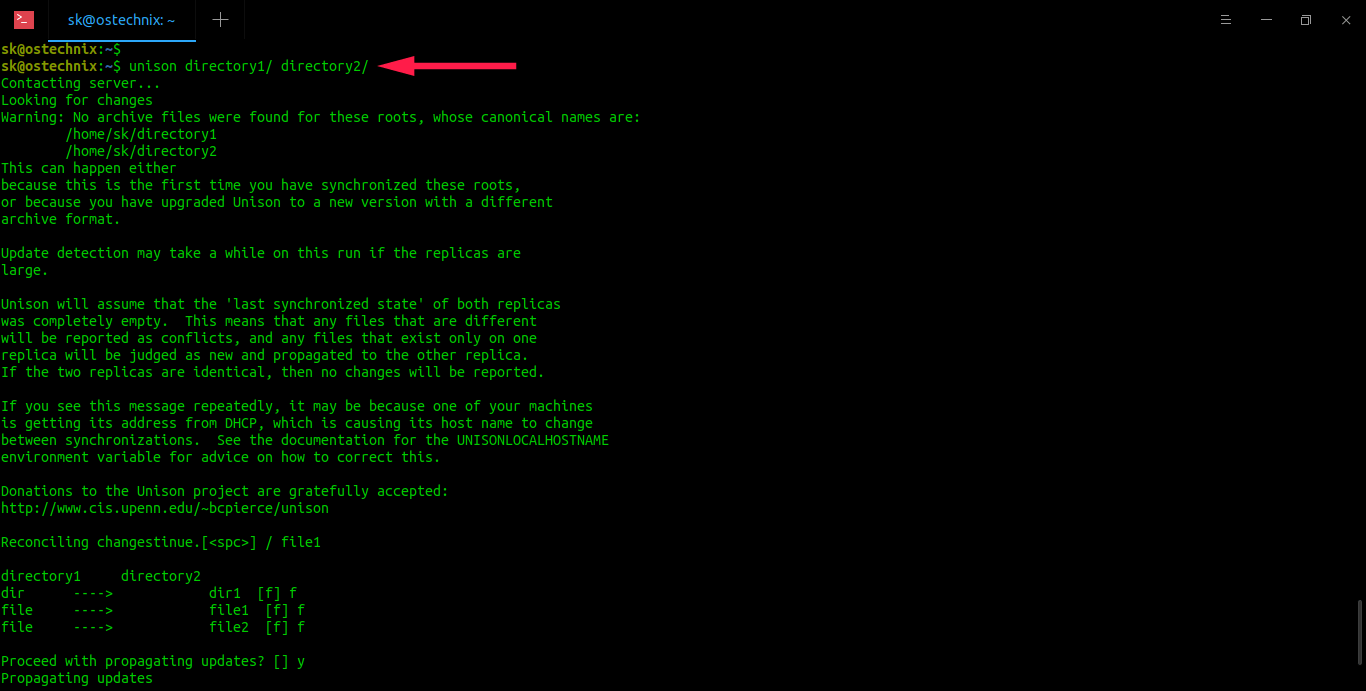

#UNISON SYNCHRONIZER SOFTWARE#

Rsync is software that performs a one-way synchronization. However, rsync, while absolutely excellent, is not the best software to use for backup.īefore I explain further, it's important to understand what rsync is and how it works, because that will help me justify my statement above. Rsync was developed by Andrew Tridgell, the same man behind Samba in fact, Tridge has stated that he believes that he'll be remembered through posterity for rsync far more than for Samba, and he just may be right. If a user new to Linux starts asking more experienced users about a good way to backup her data, she will soon hear about a wonderful tool named rsync.

#UNISON SYNCHRONIZER CODE#

In each part, we address two critical issues: first, the relation between the informal expectations of users and our mathematical specification, and, second, the relation between our idealized implementation and the actual code base (i.e., the abstractions needed to obtain a tractable mathematical object from a real-world systems program, and the extent to which studying this idealized implementation sheds useful light on the real one).The materials on this page are under a Attribution-ShareAlike Creative Commons license. We begin with a straightforward definition of the system’s core behavior - propagation of changes and detection of conflicting changes - then refine it to take into account the possibility of failures during reconciliation, then refine it again to cover synchronization of “metadata” such as permissions and modification times. We present a precise high-level specification of Unison’s behavior, an idealized implementation, and the outline of a proof (which we have formalized using Coq) that the implementation satisfies the specification.

Unison’s code base and its specification have evolved in parallel, over several years, and each has strongly influenced the other.

We describe the specification and implementation of Unison - a file synchronizer engineered for portability, speed, and robustness, with thousands of daily users. This combination of subtlety and isolation makes synchronizers attractive candidates for precise mathematical specification.

On the other hand, synchronizers are simpler than most of their relatives in that they operate as stand-alone, user-level utilities, whose intended behavior is relatively easy to isolate from the other functions of the system. Like other replication and reconciliation facilities provided by modern operating systems and middleware layers, trustworthy synchronizers are notoriously difficult to build: they must deal correctly with both the semantic complexities of file systems and the unpredictable failure modes arising from distributed operation. File synchronizers are tools that reconcile disconnected modifications to replicated directory structures.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)